Summer 2025

Ennio Morricone A Wizard of Sound

Read this article in flipbook view

Among Ennio Morricone’s 500-plus film scores, his soundtrack to The Good, the Bad and the Ugly is the one everyone knows. Like Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony or the Beatles’ “Hey Jude,” its opening theme is embedded in the culture. The melody — ah-ee-ah-ee-ah! — imitates the howl of a coyote, and the first time we hear it, it’s played on an ocarina, also known as the potato flute, an instrument introduced to the Spanish court by Aztec musicians in the 16th century.

Why an ocarina? Because it catches the ear. Ominous, exotic, and quite beautiful, it turns out to be the perfect choice as Morricone incrementally builds his soundscape with a barrage of accelerating percussion, a roadhouse electric guitar, full chorus (at times chanting nonsense syllables), the sound of cracking whips, electronic distortion, dueling military trumpets, a whistler, and, somewhere in the middle of it all, a symphony orchestra.

The effect conjures a gang of bad guys galloping across the dusty plains in director Sergio Leone’s 1966 spaghetti western starring Clint Eastwood. That opening theme — less than three minutes long — is one of the catchiest pieces you’ll ever hear, though it’s assembled from one of the wackiest collections of spare parts imaginable. This was Morricone’s way: with the intellect of a puzzle maker and a supreme gift for melody, he had a sonic fingerprint. He was a wizard of sound.

Born in Rome in 1928, Morricone came from a working-class home. His mother, Libera, ran a fabric business; his father, Mario, was a trumpeter in light classical orchestras, playing waltzes, marches, operatic excerpts and popular tunes — all of which seeped into Ennio’s ear. He began composing at age six and took up the trumpet at 11. He attended the National Academy of Saint Cecilia, the prestigious Roman conservatory, studying with Goffredo Petrassi, a stern and influential composer. There, Morricone learned to untangle the intricate counterpoint of late Renaissance and early Baroque composers. Puzzle-like counterpoint would characterize even his strangest scores.

He played trumpet in hotel orchestras, sometimes subbing for his father. As he began his career in the 1950s, he arranged tunes for pop vocal groups and composed for RAI, Italy’s national broadcasting service. Crucially, he also attended a seminar by composer John Cage in 1958, whose allegiance to silence and pure noise affirmed Morricone’s own musical vision.

For a dozen or so years — starting in 1964, when he was already established as a film composer — he played trumpet in an improvisational, and sometimes notorious, avant-garde ensemble: Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza, known as Il Gruppo.

Blat! Splat! Boing! “Somehow the noises were music,” he once said. His scores featured rattling tin cans, buzzing flies, ticking wristwatches, gunshots, and creaking ladders. Morricone could make a string orchestra mimic a swarm of angry bees — or swoon like Mahler. A lifetime of musical experiences teemed through his soundtracks, and he composed constantly — 21 scores in 1969 alone. If he sometimes seemed distracted, there was a reason: “My head is filled with music,” he said.

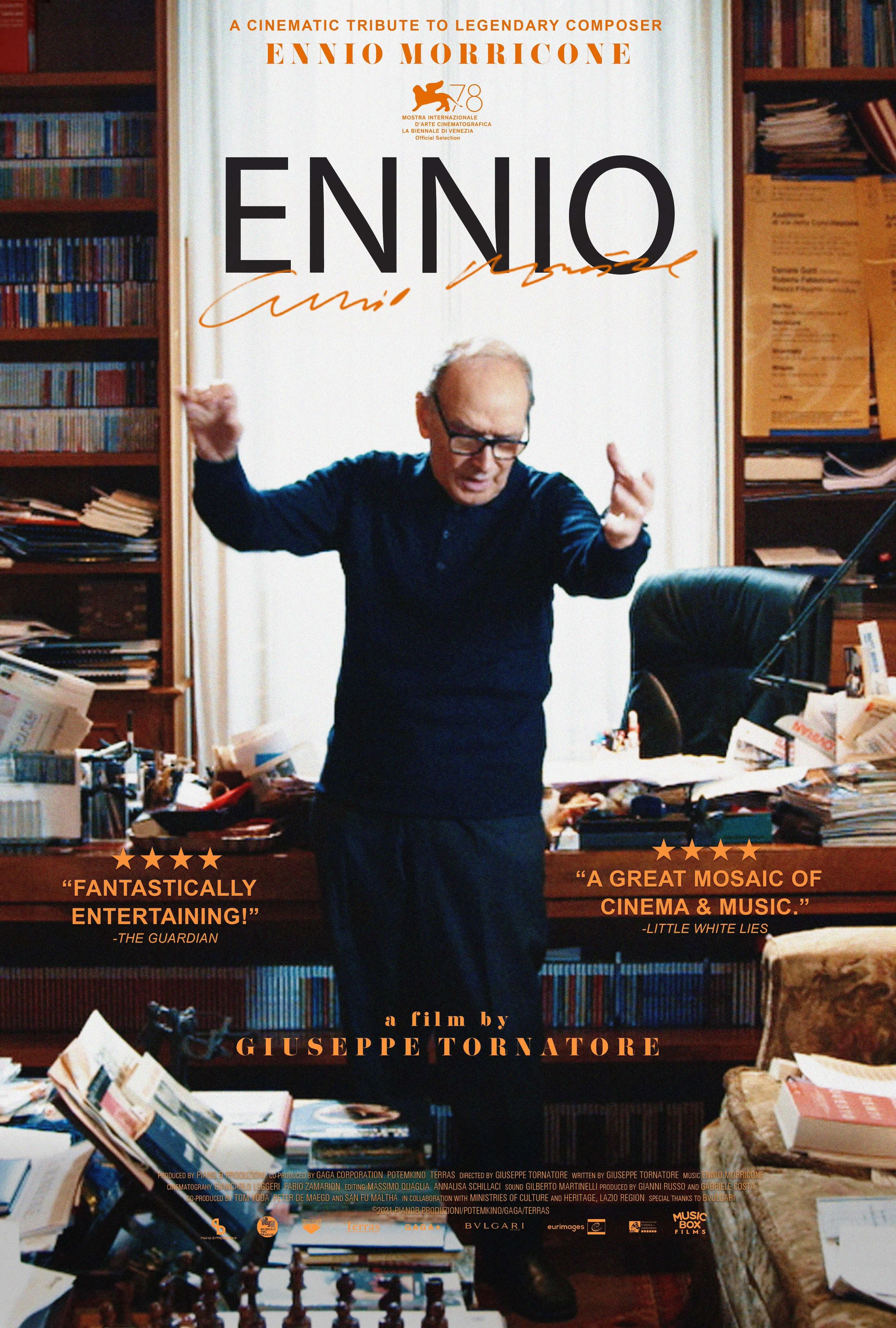

Ennio, the 2021 documentary directed by Giuseppe Tornatore (screening July 6 at Festival Napa Valley), captures Morricone’s impact on mainstream culture. It features interviews with Bruce Springsteen (who won a GRAMMY Award for his recording of Morricone’s Once Upon a Time in the West) and Joan Baez (who co-composed the anthem “Here’s to You” with Morricone for the 1971 film Sacco & Vanzetti).

Director Bernardo Bertolucci, who collaborated with Morricone on numerous films including 1900 and Before the Revolution, appears in the film, marveling at the composer’s instinctive genius: “His talent instantly rushes out,” Bertolucci says in the documentary.

“He can instantly create a song like Verdi, and you wonder what opera it’s from. But it’s not an opera. It’s Ennio.”

Morricone scored epic historical dramas, comedies, horror films — collaborating with an all-star list of directors: Pedro Almodóvar (Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!), Brian De Palma (The Untouchables), Roland Joffé (The Mission), Barry Levinson (Bugsy), Édouard Molinaro (La Cage aux Folles), Terrence Malick (Days of Heaven), Mike Nichols (Wolf), Pier Paolo Pasolini (Salò, or The 120 Days of Sodom), Roman Polanski (Frantic), and Quentin Tarantino (The Hateful Eight, which won Morricone an Oscar). And, of course, Sergio Leone, his childhood schoolmate.

![]()

Both experimentalist and entertainer, he scored everything from The Battle of Algiers (1966) to John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982). He had an extraordinary range, and yet each piece was unmistakably stamped with the Morricone fingerprint. Across a career spanning more than 50 years, Morricone also composed over 150 concert works.

There is a universality to Morricone’s music. Listening to the “Love Theme” from Cinema Paradiso (co-composed with his son Andrea Morricone), one feels the purest nostalgia, as if the music is both far away and yet so close to home that it seems to emerge from one’s own memories. This, too, is part of his fingerprint: his music created entire worlds, independent of the films it accompanied.

Consider Leone’s Once Upon a Time in America — a violent gangster film — yet Morricone’s opening theme for symphony orchestra is hushed, filled with silences and pauses, conveying wistfulness, weariness, and mourning. He might as well have been composing a Requiem.

How did he do it? His head was filled with music.

Maria Manetti Celebrates La Dolce Vita! Honoring Ennio Morricone

Tuesday, July 15 | 6:30PM

Festival Napa Valley Stage at Charles Krug

Film Screenings:

The Films of Ennio Morricone: Ennio

Sunday, July 6 | 4:30PM

CIA at Copia Ecolab Theatre

Morricone Film Series: A Fistful of Dollars & Once Upon a Time in the West

Monday, July 7

A Fistful of Dollars | 6:30PM

Once Upon a Time in the West | 8:30PM

Jarvis Conservatory

Morricone Film Series: Cinema Paradiso

Tuesday, July 8 | 6:30PM

Jarvis Conservatory